After 25 years, Ari Shapiro, the long-time NPR reporter and host of All Things Considered Over 25 years, retired in September 2025.

I like to read the memoirs of journalists because 1). you pick up good lessons and tips for how to be a journalist. This is really valuable if you (me) strive to work in media.

2). Ari has lived a splashy, exciting life. From interviewing writers, musicians, artists, and being in a band himself in Pink Martini, or making a show with actor Alex Cummings. He’s also reported from war zones, lived abroad. He has that steady and curious voice. Listen to his farewell:

Published in 2023, his book offers some of the best lessons and overarching connections from his whole career. His writing didn’t flare with literary language, or hit me with a masterpiece of art, but above all, the lessons and ideas Ari infuses into this straightforward themed chapters made me want to be a better media maker.

Part of being in media — on any level — is representing a piece of the world. You bring ideas and voice and events to the table. Providing platform and space to record what’s important about the world.

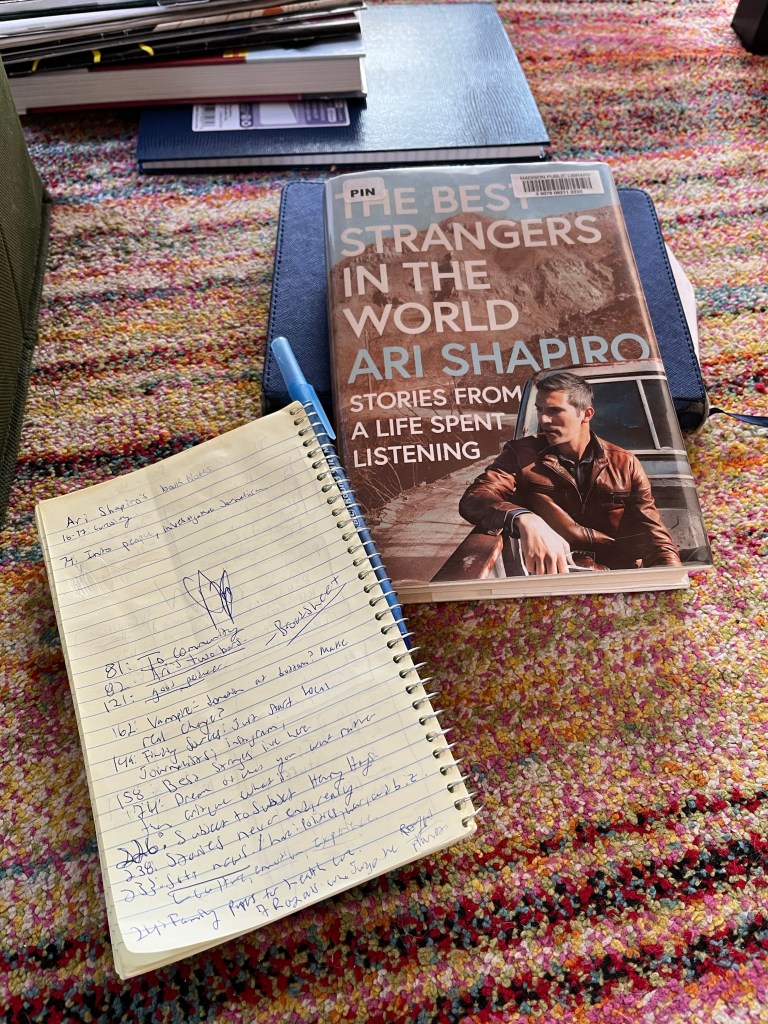

Here’s some of the best stuff I pulled from the book:

Curiosity is a skill

Ari was a curious child, and for years he felt that was more a flaw than a skill:

I never thought of my curiosity as a skill. Hiking and tide-pooling weren’t covered in any classes I took, and they’ve never appeared on my resume. But today, when journalism students or interns ask me the most important trait for a reporter, I always give them the same answer: curiosity. It doesn’t matter whether you’re curious about nature, or people, or finance, or politics. The best journalists are people who always want to learn more, who enjoy the feeling of moving from ignorance or confusion to understanding.1

Before reading these words, I too never thought of my curiosity as a trait or skill — not something I could cultivate and celebrate as something I could use professionally. Curiosity just felt frivolous. But reading these words has shifted how I approach my own curiosity, and how I might feed it. If there is one thing I wish to take from this book, it’s this shift in thinking. It’s a freeing thought to treat my curiosity as a skill. To encourage my own curiosity.

In so many ways, curiosity is why I read so much or enjoy reading (Ari also thinks this is an important trait for producers2. It’s why I enjoy exploring; this has driven much of what I’ve written about, too.)

Building on that idea, Ari, in part, rejects — or holds at a distance — what I call journalism’s Big Three: politics, war, and business — the dry hot facts that drive a frenzy of interest (and commerce).

Rather, Ari looks beyond the Big 3, and more off-the-beaten path. “Instead I gravitate toward investigative reports, profiles, and articles that illuminate the entire world by zooming in on a tiny sliver of life.”

This is interesting as Ari spent time as a White House correspondent, flying on Air Force One, being in the “bubble” of reporters that followed the President. Ari struggled to see how he could make the coverage interesting. But he brought that curiosity and different angles to the biggest of the Big 3. As President Obama addressed a press corp in Pensacola, FL after the BP oil spill in 2010, Ari visited a local hangout, a water front oyster bar, Peg Leg Pete’s to get the local reaction. “I wasn’t talking about the impact of the oil spill was having on a community. I was talking to members of that community,” Ari wrote.3

Near the end of the book, in the final chapter, Ari sums up his feeling on the Big 3: “…I do care about politics, war, and business. I’m happy to interview a senator or a cabinet secretary about the political controversy du jour, and I understand why that is important part of the mix of stories that we tell. But I think news organizations often make a mistake by valorizing those bone-dry interviews over flesh-and-blood stories of culture, emotion, and personal experience.” Borrowing from his friend Sam Sanders, Ari believes “soft news” is just as important as “hard news” (Business, War, Politics). There is an artificial divide.

Another strong lesson here: journalists, media makers, should pay attention to the culture stories, the personal stories, the every day life. Because to suppress those stories means you’re suppressing voices, keeping them off the platform – keeping out important parts of life, and lives of individuals. You can’t understand the hard news unless you understand the emotional potency and the cultural significance — all stuff that lay in the gushy heart of “soft stories.”4

It’s an honor for a stranger to let you into their life.

It’s always good to remember that any person who talks to a media maker, a journalist, doesn’t owe the journalist anything. Subjects, people talking into recording devices are doing the recorder, the scribe, the journalist a favor. They are allowing access and allowance.

This is the big theme of Ari’s book, and another big take away.

On page 82, Ari talks about one of his reporting philosophies, that with every story there are two bars: The low bar is when you have something to post/put on radio/write about. This is the low hanging fruit. The press release remix, the event promotion, the audio from a conference, the quick interview from the most accessible person. You have a fact, something that makes a sound, but not music.

“The second bar,” Ari wrote, “is the platonic ideal of a perfect work of journalism.”

It is vivid, surprising, transporting, distinctive, and true. Every finished story falls somewhere between those two bars. During my four years on the White House beat, I may have spent more time near the lower bar than the higher bar. But knowing that I constantly had that reach goal, thinking every day baout how to get closer to the higher bar, kept me motivated.

How do you find those folks: You just get started. You ask, send messages, hop on social,make phone calls, go places. You just get started in finding sources.5

Lastly, a reoccurring them for Ari is this debate if journalism is a vampiric enterprise. Using other people to create content. I’d argue that’s Big Social. Meta, X, and now OpenAI use user content for personal gains. Journalism has versions of this — begging someone to share a story so it can be exploited and hit the high note of the news cycle.

But Ari shows how he revisits subjects and people, checks in with them. He tries to have care with others. The title of this memoir comes from a piece of art that states The Best Strangers in the World Live Here.

I thought of the time I had spent overseas and the thousands of peope I’d met who trusted me to tell their stories — indeed, the best strangers in the world. As I looked at the artwork, I resolved to explore the US with the same curiosity that I had approached other countries during my time abroad. 6

Almost always, a person who gives an journalist a story, information is a stranger — and out of that the story may serve the public: inform, change a mind, record a moment for history — make others feel less alone. The best strangers for Ari are the ones brave enough to chat with him on mic. Ari later brings up the gay rights activist Harry Hay and his idea of “Subject to Subject” relationships.7 For a journalist and subject (a person being interviewed or asked for information) is at it’s core a relationship. It’s up to the journalist to decide if it’s going to be a relationship where the journalist treats that person and their information as a object, or another living, flesh-and-blood subject.

Artists offer the most clarity, especially writers.

A surprising chapter was when Ari talks about the power of artists, and their importance to the world. It was a breath of fresh air and in an age of fakery, digital commerace, and platform lock-in, it felt good to hear that writers, fiction writers even, have a strong role to play in understanding the world:

And now that I have spent every workday for years speaking to leaders in all walks of life, I’ve reached a conclustion. The conversations that help me see the world most clearly are generally not with researchers, policymakers, or so-called experts. They aren’t with the people journalists crassly call “newsmakers” at all. They’re with artists — especially writers.8

It’s the great irony that through art — through creations of imagination — we can get truth. A sci-fi and fantasy work or a thousands of years old myth, can tell you more about a lived experience, get at the heart a human experience. It becomes a way for people to perhaps engage with the biggest challenges and celebrations of our lifetime.

Ari may be a Yale graduate, and come from a place of advantage, but I think anyone with the desire to make media — to be something related to a journalist — can learn from him. It’s worth the read for these lessons buried in the text like chocolate treats for the hungry-to-learn mind. Lessons in how to listen, how to find truth, and how to have fun.

P.S. Produced in 2003, one of Ari’s breakout reports was about the history of the sandwich. It’s a quirky, fun, and yet, an informative listen. Here it is:

Leave a comment